The supermodel, the hipster and the goonda do Dharavi

Apr 7, 2013 – Bombay is many things: preternaturally cramped, exhilarating, dirty, vibrant, sweaty, energetic, and overwhelmingly odiferous. It’s a place of industry and high expectations, of seedy lowlifes and the promise of better things; it is South Asia’s New York, and probably the New York of the new world order. It’s where dreamers go to try their luck and where everybody goes for their personal slice of freedom, in whatever form that takes.

But go to Bombay during monsoon time and a different mood takes hold. Heavy grey storm clouds hang low over the city and air doesn’t flow nor move, the stench of rotting garbage fills the air, and stray dogs and armies of crows fight for space at overflowing rubbish skips. It is at times almost as though the mountain of garbage threatens to take over the city, slowly engulfing apartment buildings, people, like a tidal wave of refuse. In place of a sea breeze the air is stagnant, feels cholera-thick.

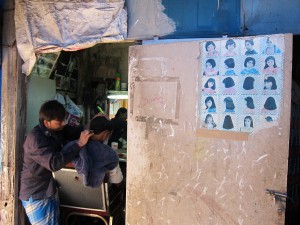

In mid-2011 the editor of Motherland, a new magazine on Indian subcultures, contacted me. The upcoming issue would be themed around ‘ecology’ in its various definitions, and did I have any ideas? Immediately I thought of Dharavi: essentially, how the notorious neighbourhood has moved beyond the simple definition of being a slum and in reality is a thriving, humming centre of commerce and industry, albeit in exceptionally cramped quarters. With roughly a million people crammed into just over one square mile, Dharavi’s industries create $US665 million in turnover each year. It has schools, hospitals, cinema halls, and much of what is produced there is consumed locally. Like an ant colony, Dharavi is a self-sustaining ecology all of its own.

The story turned out to be a tough sell as Dharavi is possibly the most overexposed of India’s million mutinies; however I’d managed to find a coterie of philosophical urban planners based there which added a much-desired hipster element to the story, in line with the magazine’s mores. But I had a tight deadline and it was monsoon season, with a high chance of rain. I really, really did not want to be in Dharavi when a downpour struck.

My photographer on the piece was Sheetal Mallar; one of India’s top supermodels in the 1990s and 2000s, and now transitioning to a career behind the lens. Just how would a supermodel fare in Dharavi? She assured me she was looking forward to the shoot and doing grittier work, however had never visited Dharavi despite having lived in Bombay her whole life.

After meeting at her flat in Bandra, waiting out the rain over pao bhaji on Hill Road and haggling for an auto, we arrived at one of Dharavi’s borders, 90 Feet Road: me, Sheetal and her assistant, whose young face fell into a dour scowl when he realised our destination and subject. He hadn’t been told the assignment in advance, and was dressed for a day in Bandra with a supermodel in skinny jeans and leather booties, and certainly not skipping around a muddy slum. “He’s a bit angry with me,” said Sheetal, smiling shamefully.

Our first stop was at the office of Reality Tours, a UK-Indian duo who’ve been running highly successful slum tours for a few years now. Krishna Pujari, one of the founders, had agreed to take us in and give us a start: to be able to walk through Dharavi you need to be accompanied by a known face; it would have been overly intrusive of us to be walking through with our cameras without a guide. Krishna was going to introduce us to a few people, and after a while, leave us in the hands of someone else, who, ideally, would pass us on to someone else.

Things went to plan this way, for most of the three days we spent there. We managed to avoid getting wet, ducking into godowns or tiny offices when it rained. At one point on day one we exited yet another narrow gully onto a main road that borders Dharavi and found a murky stream, obviously full of raw sewage, with a pipeline leading down to it. That was my cue to leave for a break, but Sheetal stayed behind to photograph, a true trouper. Her hipster assistant remained with her, his face stony, occasionally wiping the soles of his leather shoes on a sharp ledge. He didn’t talk much to us throughout the entire assignment.

Things went to plan this way, for most of the three days we spent there. We managed to avoid getting wet, ducking into godowns or tiny offices when it rained. At one point on day one we exited yet another narrow gully onto a main road that borders Dharavi and found a murky stream, obviously full of raw sewage, with a pipeline leading down to it. That was my cue to leave for a break, but Sheetal stayed behind to photograph, a true trouper. Her hipster assistant remained with her, his face stony, occasionally wiping the soles of his leather shoes on a sharp ledge. He didn’t talk much to us throughout the entire assignment.

As always, what happens behind the scenes, and the people we meet, rarely make it into the commissioned story. Here, I had a strict brief to follow and just 1,800 words to play with. So Shekhar missed out on being inclued.

Shekhar was the local teenager who took responsibility for guiding us around the place towards the end of our Dharavi tour, leading us from one section over a rail bridge to another, and pointing out where bits of Slumdog Millionaire was filmed. Shekhar described himself as a freelance photographer, filmmaker, DJ, writer, tour guide and ‘student of life’. (His sister was studying for her MBA, meanwhile.) He learnt his various trades from the conga line of firangis who wind up in Dharavi, either by accident or design, and stay for a while. For some months, a Spanish filmmaker called Jesus moved into the shack his family calls home. They have always lived in Dharavi, a place Shekhar loves, for despite the smells, the cramped living quarters, the bathrooms shared with dozens of neighbours, despite the lack of any kind of personal space whatsoever, it was in Dharavi that he has learned what life is, and constantly meets people who challenge and teach him.

Shekhar is wiry, square-jawed and dark-skinned, and smoked his cigarettes in a self-conscious ganster style, clasped between his thumb and forefinger. His family is part of Dharavi’s sizeable Tamil population, which first settled in the area about a century ago. Still, the community celebrates the southern Hindu religious festival of Thaipusam, famous for its gory displays of metal rods pierced through men’s cheeks and hooks through the skin of their midsections. Shekhar had taken part the previous year, and described how he had pierced large hooks into the skin on his back, then was lifted by the hooks by a crane high above 90 Feet Road. “It was the best day of my life,” he said, reverentially. “Everyone was looking at me, waving and applauding. Women were passing their babies out of the windows for me to hold.”

Would he do it again? “No. People would think I’m showing off.”

He helped us find the offices for Urbz, the urban design duo headquartered in Dharavi. The pair, a Swiss-Spaniard and an Indian, only set up their office in Dharavi because they couldn’t afford anywhere else. Indeed, they could barely afford Dharavi but managed to find one of the many illegal second-floor constructions that was within range: one of the great stories of modern Dharavi is simply how unaffordable it has become. Middle-class Indians – like Krishna Pujari – wouldn’t mind living in Dharavi as it’s so central and well-served by trains, but are finding they can’t afford it.

At Urbz, we listened to the pair divulge their knowledge of Dharavi’s urban fabric and how it is really no different from slum areas anywhere else in the world. There’s a pattern, they said, to how slums develop. First, they look like Dharavi. Then they get cleaned up, gentrified, homes are built with proper foundations and materials and essential services are brought in, but the areas retain their cloistered nature. Then they told us how Dharavi has moved on from its former reputation as a haven and hiding place for Bombay’s underworld, pointing out that community links are now so strong that anyone doing anything unacceptable, for example beating their wife, would be dealt with strongly by their neighbours. When walls are that thin, there’s no place to hide. It was a fascinating, eye-opening discussion that left me feeling assured that Dharavi was going to go places. “We should all be looking at this place and learning lessons about how people will live in the future, because this is the reality,” said the Urbz guys. Now that the dark underbelly had been swept away and some large-scale gentrification projects, however controversial, are taking place, Dharavi might well become a model neighbourhood.

As we walked out, Shekhar looked nervous, and started walking fast towards the main road. We scurried to keep up.

“I don’t know why they’ve chosen this bullshit neighbourhood. Everyone keeps staring at me,” he said.

“I thought Dharavi was a friendly place with no social problems anymore,” I said.

“Not here. This gang and my gang, from my area, are fighting.”

“Why?” I asked.

It all started with a girl, he explained. “First one boy got beaten up from my side. Then we came here and beat up some people. Then my friend’s father killed someone. Now he’s in jail, and if I come over this side I get dirty looks.”

Then Shekhar stopped, and turned and beckoned for me to come closer. Quietly, in my ear he said: “You want something done? Someone done? Call me. I can get these things done for you.”